Knots and DNA: part 1

July 29, 2025

Part 1 – General Information about DNA and Knotted DNA

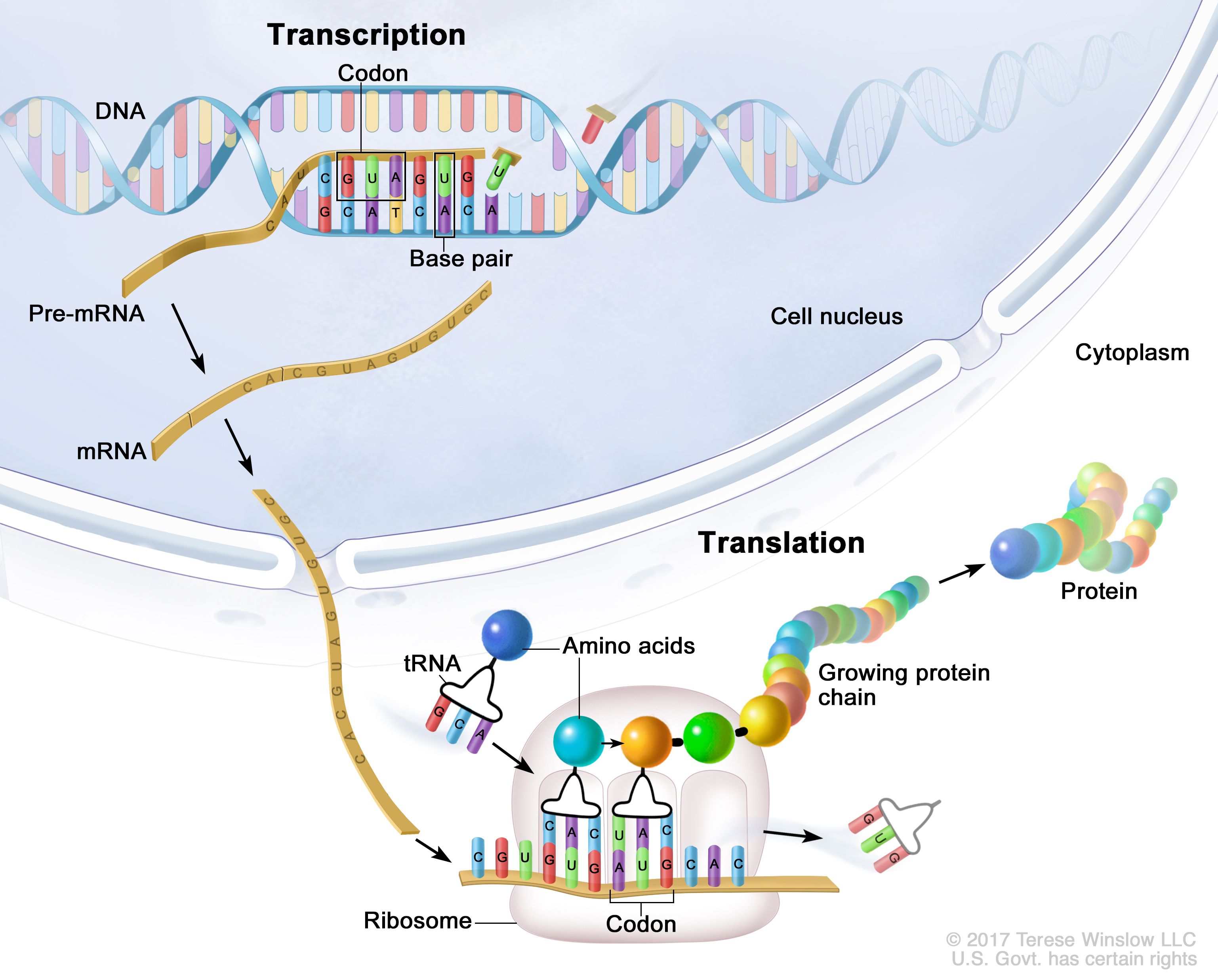

Our genetic code is stored in a long and beautiful molecule called DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid). It contains the information necessary for protein production, written in an alphabet consisting of four letters (known by their conventional labels A, T, G, and C), or building blocks called nucleotides. This code is read and transcribed into RNA, which is later translated into the desired protein.

Simple, isn’t it?

Deceptively simple, as becomes clear when we look closer. Let’s focus on the reading part: since the mid-1950s, we’ve known that DNA is a double helix, and that nucleotides pair complementarily (A pairs with T, and C pairs with G). This means that DNA consists of two chains of nucleotides, two complementary strands paired and twisted together. Enzymes must read the genetic code, aka the sequence of A,C,G and Ts, on only one of these strands. For this to happen, the strands must first be separated by unwinding the double helix and unzipping the strands. As we can easily imagine, the more the strands are separated, the more the twisting shifts along the molecule, creating increasingly tangled clumps. These tangles would jam the DNA-reading machinery, potentially disrupting RNA production and, as a downstream effect, protein assembly, ultimately impairing cell function.

Yet this does not happen!

Nature has evolved countermeasures to deal with these tangles! How? Again, using specialized proteins. There are enzymes called topoisomerases whose task is to untangle DNA through “cut and sew” operations. The simplest type cuts one of the two strands of the helix, relaxes the accumulated twisting by rotating around the other intact strand, and then "sews" it back together. Even from this brief overview, a very dynamic perspective of DNA emerges, which is subjected to incessant enzyme actions that separate the strands, transcribe the genetic code, cut and sew one or both strands to relax the accumulated twisting. As good as that sounds, it doesn’t come free from side effects. All these operations inevitably introduce errors or defects, for instance, knots in the DNA strand.

Knots cause very serious problems for DNA transcription and replication because they are insurmountable jamming points for molecular machinery. In general, they are lethal for the cell (unless you are a specific cool parasite that makes tangles its superpower). Again, nature has devised countermeasures: other topoisomerases that cut both DNA strands. These topoisomerases identify the “crossings” of knots (you can't make a knot in a rope without it crossing itself) and act by reversing them, again using a cut-and-sew operation.

Even here, their action is deceptively simple.

To understand this, we must consider that these enzymes are just slightly bigger than the thickness of a DNA strand (a few nanometers) but are 100 times or more smaller than its length. Since DNA knots are not tight but spread over a good part of their length, we immediately understand that the task of topoisomerases is difficult. It is as if we were blindfolded and had to untangle a very long rope by feeling for the points where the rope crosses itself and making local cuts and stitches. We understand that this is a daunting task when you cannot see the rope as a whole. In fact, cutting and sewing indiscriminately at all crossings within reach would end up introducing many knots instead of removing them.

The precise mechanism of topoisomerase action is still unclear to us because it cannot be observed under a microscope, so we can only formulate hypotheses, and among them, the prevailing one is that the correct crossings have unique geometric properties that enzymes can easily recognize. This is a very plausible, simple, and fascinating hypothesis.

Takeaway: DNA is not just a static code but a dynamic molecule that can get tangled during important processes like copying and reading. Special enzymes called topoisomerases help untangle these knots by carefully cutting and rejoining DNA strands, ensuring the cell’s machinery keeps running smoothly.

Part 2 – Computational Study

However, another problem arises due to the incessant thermal agitation motion that pervades all matter, including biological matter. In practice, DNA is always in motion, so how can enzymes recognize precise geometric features if these are continuously changing? Because we can’t watch enzymes at work directly, deciphering the mechanisms that untie DNA knots can be done through computer simulations. The basic idea is very simple: simulate reality with the laws of dynamics that we all encountered in high school, but far more detailed.

In simulations, every atom of the DNA has a position in space, thus three coordinates (x, y, z). By applying the laws of physics, we can track how these atoms move over time, a bit like following the parabolic path of a projectile you once drew in a school notebook. The difference is, instead of a single bullet, we have thousands upon thousands of them, all interacting, and we need to keep track of every one!

Obviously, we can have different levels of detail. We can consider one point for each atom, or we can describe the movement of a group of atoms with a single point, for example, those forming a nucleotide. This type of generalization, although it loses detail, has advantages in speeding up calculations dramatically, as we do fewer computations, reaching microseconds or even milliseconds of simulated time. And keep in mind, a millisecond is still much faster than a blink of an eye!

Another advantage of not looking at atomic detail is that it allows zooming out and seeing the big picture. And it is in this big picture that we see whether there is a knot, or whether DNA is supercoiled on itself. These are global properties that are not measurable on a single atom. The ability to supercoil is a consequence of the torsion accumulated in the double helix when opened and pulled by enzymes, and it is roughly the same effect as when playing with a telephone cord, where you create curls that keep the wire much more compact. (And yes, the choice of analogy might reveal that global property known as the age of the writer!)

Using this scheme, we simulated DNA when it is supercoiled and knotted at the same time, and we saw that when both are present, the knots stay pinned to a specific part of the molecule while the rest remains supercoiled. A second effect, just like in the telephone cord curls, is that supercoiling, when present, concentrates all the crossings closer together, making them easier to find. This seems to give enzymes more time to recognize the knot and act to untie it, instead of looking for it while it moves along the entire DNA, which is very long!

Think about it, the bacterial DNA we considered is about 680 nm long and 2.5 nm wide, which means that if DNA were 1 cm thick, it would be about 3 meters long, and the enzyme that has to remove the knot would be no bigger than a 2-euro coin tasked with finding the right spot to untie the knot.

Takeaway: DNA behaviour can be modelled via computer simulations at various levels of detail. These simulations reveal how DNA twists and knots behave, helping us understand how enzymes locate and fix knots efficiently despite DNA’s constant motion.

Part 3 – Knot a superpower

Generally speaking, entanglements are avoided in organisms and solved by topoisomerases. But 'generally' does not mean 'always,' and of course, there are bacteria that seem to gain an advantage from them! A very curious story involves a parasite responsible for yellow fever and sleeping sickness, called trypanosome, which has become of particular interest to the knot-study community (finally, a creature that truly appreciates a good tangle!).

Fun fact, mitochondrial DNA (that DNA stored in the mitochondria) usually comes as tiny rings, stored in a very small volume. During cell division, every ring divides into two copies, ideally one for each daughter cell. To increase the likelihood that each daughter cell gets at least a copy of each ring, cells usually keep many identical copies of these rings.

So, what does a trypanosome do? It tangles its DNA rings in order, probably because of confinement. Think of it like a chainmail shirt, all the little rings are hooked together just right. This means the DNA gets copied and divided up neatly, not randomly. Because everything’s so well-organized, the cell doesn’t need as many copies, which saves a lot of energy, and therefore makes it a more efficient parasite.

This fascinating phenomenon, studied in detail by F.J. Arsuaga’s research group, highlights just how important it is to understand the topological, or shape-related, properties of the genome. It’s not just about the genetic code itself, but also about how the DNA is physically arranged and organized. The way these DNA rings are linked and tangled can have a big impact on how efficiently the genetic material is copied and passed on during cell division. Understanding this 3D organization helps uncover new insights into cellular function and could even lead to advances in treating diseases linked to DNA organization.

Takeaway: while knots are usually harmful, some organisms like trypanosomes use tangled DNA to their advantage. Understanding DNA’s 3D shape is crucial for insights into biology and disease.

Sources:

Lucia Coronel, Antonio Suma, Cristian Micheletti, Dynamics of supercoiled DNA with complex knots: large-scale rearrangements and persistent multi-strand interlocking, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 46, Issue 15, 6 September 2018, Pages 7533–7541, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky523 Diao, Y., Hinson, K., Kaplan, R. et al. The effects of density on the topological structure of the mitochondrial DNA from trypanosomes. J. Math. Biol. 64, 1087–1108 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00285-011-0438-0 Notes This text is based on the radio interviews aired on July 31, 2018. It has been translated and expanded for clarity and completeness.